Along the drive south from Rockford along the meandering two-lane [amazon_textlink asin=’0791815641′ text=’Illinois Highway 2′ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’0ee5e24b-6f46-11e7-b25b-35dcc999abae’], the scenery recalls a bucolic Midwestern past: miles of prairie and forest interspersed with small towns and farmsteads.

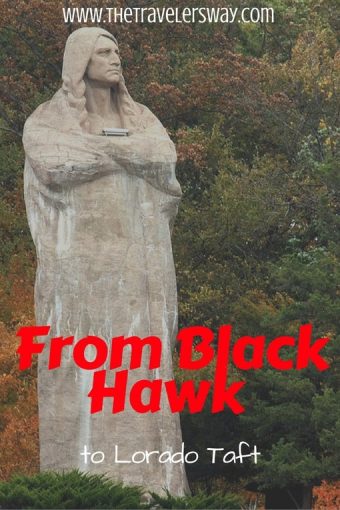

Then, a couple of miles north of Oregon, [amazon_textlink asin=’1741799023′ text=’Illinois’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’2b794137-6f46-11e7-9c0f-47965264aef9′], “The Eternal Indian” (also known as the Black Hawk statue) comes into view. Standing 50 feet tall on top of a 77-foot bluff overlooking the Rock River, the monumental sculpture surveys the land and river native tribes once roamed. The statue, which weighs 536,770 pounds, is said to be the second largest concrete monolithic statue in the world (the largest is probably Christ the Redeemer, towering over [amazon_textlink asin=’1743217676′ text=’Rio de Janeiro’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’adcfd7ef-6f47-11e7-a139-59973d3fbdf0′], Brazil, at about 100-feet tall ).

The body of “The Eternal Indian” (right) is hollow but the head contains the ends of 24 reinforcing steel rods and is cast in solid concrete. You can pull into Lowden State Park for a closer look — not only of the statue but the view. In 2009, the Black Hawk statue was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

In the 1830s, after many skirmishes culminating in the [amazon_textlink asin=’1502964759′ text=’Black Hawk War’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’4c1d462a-6f46-11e7-8336-3db9aa4ddc24′] (the last war fought against Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River), the Potawatomi, Winnebago and Sauk Indians who had lived in the region for centuries retreated west across the Mississippi River and ceded the land to the incoming European-American settlers.

The statue is informally called Black Hawk, for the famed chief of the Sauk tribe during the war bearing his name. (He’s a popular symbol of the Native American past in this part of Illinois – the Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League were named in his honor.)

The majestic figure was erected between 1908 and 1911 on land that was then part of the Eagle’s Nest Art Colony – a sort of artists’ summer camp founded in the 1890s that centered around famed sculptor [amazon_textlink asin=’0259439800′ text=’Lorado Taft’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’6d52dbd2-6f46-11e7-bb06-fb4c0908310a’] (1860-1936), creator of “The Eternal Indian”. Anxious to flee the heat (and probably the stench) of Chicago summers, the charter group – it started with eleven men — first lived in tents at the colony. Later, members were allowed to build summer homes at the site.

Adjacent to the park, you can wander the colony site and see some of the original structures that are now part of Northern Illinois University’s Lorado Taft Field Campus.

Two miles south is the sleepy little town called Oregon (population about 3,600) that straddles the Rock River less than 100 miles due west of Chicago.

The more famous Oregon on the West Coast got its name in the 1790s (the word is said to be of Algonquian origin and means “River of the West”). This hamlet was named in 1838, perhaps as a playful reference to its location on a river to the west of New England, where most of the early settlers originated. They began farming in an area long inhabited by a succession of native tribes, who left behind a large number of ancient mounds, most 10 or 12 feet in diameter.

You can see surviving mounds from the Hopewell culture (about 200 BCE to 300 CE) nearby at Albany Indian Mounds State Historic Site along the Mississippi River.

Taft and his fellow artists had a lasting impact on the small town. Two of the charter members of the art colony were Chicago architects: Allen and Irving Pond. They designed the Oregon Public Library with a second story art gallery intended for art shows and lectures in 1907, and it was constructed with a donation by industrialist [amazon_textlink asin=’0451530381′ text=’Andrew Carnegie’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’9f8ef6ff-6f46-11e7-89b7-8b6c172e5799′].

The gallery – open upon request — is filled with more than 50 sculptures and paintings as colony members donated representative works for display, including a plaster working model of “The Blind” (above) by Lorado Taft.

Although the Eagle’s Nest Art Colony closed in 1942, its legacy continues. The Oregon Sculpture Trail is a mostly outdoor collection of works throughout town by many artists – including Taft. His Soldiers’ Monument sits on the lawn of the Old Ogle County Courthouse (below). The Fish Boys is a concrete replica of Taft’s bronze sculptures from “Fountains of the Great Lakes” in the South Garden of the Art Institute of Chicago. Local sculptor Jeff Adams created Paths of Conviction, Footsteps of Fate, which reflects on the crossing of the paths of Abraham Lincoln and Chief Black Hawk during the struggles in this area in 1832 – and there are a dozen more.

Train buffs will want to make a stop at the Oregon Train Depot, constructed in 1913. It’s under restoration but tours can be arranged. The town had great passenger train service in the first half of the 20th century, perhaps because its congressman was married to the daughter of Chicagoan [amazon_textlink asin=’1439262314′ text=’George Pullman’ template=’ProductLink’ store=’thetravelersway-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’ba2f1179-6f46-11e7-867a-83fec3cdc924′] (he of Pullman sleeping car fame).

Vintage toys, sleighs, farm equipment and other relics of the past are on display in the Billy Barnhart Museum, located in Conover Square – Oregon’s mini mall, a former piano factory reconfigured to house locally owned businesses, shops, a bakery, and café. A wide selection of contemporary Native American artwork, jewelry, crafts, apparel and home décor are offered at the Eagle’s Nest, a shop along the Rock River near downtown Oregon.

(Featured photo of “The Eternal Indian” courtesy of the Blackhawk Waterways Convention & Visitors Bureau; all other photos by Susan McKee)

For Pinterest:

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. Clicking through for additional information or to make a purchase may result in a small commission being paid. By doing so, you help support this site and its authors, at no additional expense to you. We thank you for your support.

You might also enjoy

Susan McKee is an independent scholar and freelance journalist specializing in history, culture and travel.

What a fascinating bit of history. I lived in the West Coast Oregon for years but never knew about the other one in the U. S.

Lovely post about an area that I love. Please do not wander through the old artist colony site, however. It is now an outdoor education and conference facility and is closed to the public. Stop in the office first and make sure it is ok for you to be there. Thank you.

There’s an update on conservation efforts for the Eternal Indian:

https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-met-eternal-indian-black-hawk-statue-restore-20181108-story.html