February 3, 1959 — 62 years ago — a small plane crashed into a snowy farm field near Clear Lake, Iowa. The plane’s pilot died, along with singer/musicians Ritcie Valens, J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, and Buddy Holly.

The first two have faded from memory, but Buddy Holly, just 22 when he died, has had an outsized influence on the popular music scene. Of course, the crash was immortalized in “American Pie”, a song and album by American singer and songwriter Don McLean that was released in 1971, but his legacy goes much beyond that.

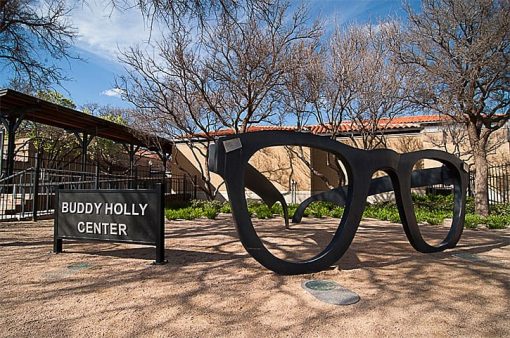

This weekend (February 1-3, 2019), commemorating the 60th anniversary of his death, the Buddy Holly Center in Lubbock, Texas (his hometown) has planned three days of activities celebrating their favorite son.

Here are some of the details I learned about Holly on my visit to the museum in the center.

- He’s considered the bridge between rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll. In 1955, Holly saw Elvis Presley perform; in 1958, musicians who became the Beatles saw him perform.

- John, Paul, George and Ringo called themselves the Beatles in homage to Buddy Holly’s backup singers, the Crickets.

- The Everly Brothers recommended Holly’s attorney (and even took Buddy to a New York clothing store to buy the “right” suits).

- Elton John, who — unlike Buddy Holly — needed no vision correction, consciously copied Holly’s signature eyeglass frames.

- Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones modeled his guitar style after Buddy’s in “Not Fade Away”.

- Paul McCartney has been to Lubbock to perform in Holly’s honor, most recently in 2014. That’s when the McCartney Tree — a multi-trunk red oak — was planted in front of the Buddy Holly statue.

If you can’t make it to Lubbock for the anniversary weekend, the city has a self-drive map of key locations in Holly’s life — and, of course, you can visit the Buddy Holly Center.

There are plenty more reasons to put Lubbock on your travel schedule, including lots of bars and night spots with lots of music ranging from country to tango and everything in between.

My favorites are:

- Prairie Dog Town. Not only are the little mammals fun to watch, but they’re a keystone species in the ecosystem of the Great Plains. The walled enclosure inside Mackenzie Park at 4th Street and I-27 doesn’t really keep the critters from escaping into the “wild”, but there’s enough of the “scurrying and burrowing” to entertain both children and adults.

The “town” was established in 1935 by local resident Kennedy N. Clapp when it was feared the black-tailed prairie dogs were headed toward extinction (it goes without saying that ranchers and farmers would rather not have their land pockmarked with burrows dug by these herbivorous rodents). Now cosseted by the Lubbock Parks Department, the colony is a popular sightseeing stop.

The “town” was established in 1935 by local resident Kennedy N. Clapp when it was feared the black-tailed prairie dogs were headed toward extinction (it goes without saying that ranchers and farmers would rather not have their land pockmarked with burrows dug by these herbivorous rodents). Now cosseted by the Lubbock Parks Department, the colony is a popular sightseeing stop. - Texas Tech University, with more than 36,000 students, influences many areas of Lubbock life. One of the most important for tourists, however, is its collection of close to 100 pieces of public art. The collection began in 1998 and is funded by one percent of the estimated cost of each new major capital project at TTU. Although there are paintings and artwork in other media, most are metal sculptures located outside campus buildings, so they’re available 24/7.

One series, “Texas Rising” by American artists Joe O’Connell and Blessing Hancock, is completely different after dark when the set of perforated stainless steel stars “rising” from the ground are lit from within by shifting colors of LED lights. An architectural theme unifies the campus, founded in 1923 — most of the buildings are brick in Spanish Renaissance style with embellishments in carved stone.

- There’s a completely different category of architecture on the edge of nearby Ransom Canyon. The as-yet-unfinished Steel House, 85 East Canyon View Drive, designed by the late Robert Bruno Jr. perches like a gigantic extraterrestrial insect on a ridge outside Lubbock. Construction on the 110-ton blackened steel edifice was abandoned when the architect died of colon cancer in 2008, and its future remains unknown.

By the way, according to Wikipedia, February 3, 1959, was not called “The Day the Music Died” until after McLean’s song became a hit in the 1970s.

McLean was 13 years old, folding newspapers for his paper route the day after the crash, and read about Holly’s death. Years later, he dedicated the “American Pie” album to Holly, and referenced his discovery in the line “February made me shiver/with every paper I’d deliver”.

(Photos courtesy of the City of Lubbock and by Susan McKee, who visited Lubbock as part of the SATW Central States meeting in 2018).

You might also enjoy

Susan McKee is an independent scholar and freelance journalist specializing in history, culture and travel.